Project 14 GOW

October 3rd – 30th October 2011

Rebecca Partridge & Revd Dr. Richard Davey

Shards of Wonder

We stand at the water’s edge on black volcanic sand. Before us interlocking patterns of foaming spume dissipate across the surface of the steel grey water towards an area of white fog that shrouds the horizon, engulfing our gaze in its indeterminate space.

Alone on a desolate mountain moor, standing on a sea of heather, rock, and grass, a blanket of mist reaches out to enfold us in its damp embrace, its gray opacity obscuring the possibility of a world beyond our immediate surroundings.

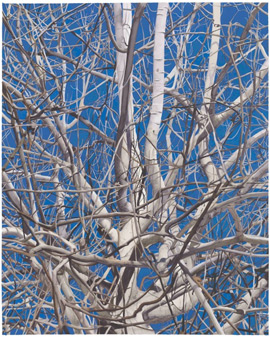

Standing in the middle of a dark forest we find ourselves hemmed in by a tangled mass of branches. We can find no escape, and so we look into the sky. There we encounter the infinite depths of space losing ourselves in the diaphanous clouds of stars that animate the velvet darkness of night; a billion suns squeezed into tiny pinpricks of light.

In December 1968 the crew of Apollo 8 took a photograph of the earth rising above the silvery grey lunar horizon; a spherical wedge of white, blue, and green floating alone in the black void. For the first time human beings could see their planet home as it appeared from deep space.

Implicit in this iconic image is the rapid expansion of technological and scientific knowledge that has shaped the modern world; the ability not only to capture a likeness in a photograph, but to journey through the silent expanse of the heavens. Yet as we gaze upon the sight of our planet as a tiny speck within the infinite, formless void our sophisticated knowledge evaporates and we experience those feelings of fear, incomprehension, awe, and intense joy that are symptoms of the sublime. Like the paintings of artists such as Casper David Friedrich, JMW Turner, and Mark Rothko that have been inspired by those awe-full moments when we are rendered child-like, this photograph also takes us to that space beyond language where words are inadequate. And it is in this experience of the sublime that we also encounter the essential loneliness of the human; the sense of difference and the realisation of the gap that separates self and other.

A shower of water droplets cascades through space where they intersect a beam of bright light. Momentarily a rainbow flashes at the edge of our vision. More showers, more darting rainbows transforming the space around us, capturing and revealing the intangible with their shifting palette of colour.

Rebecca Partridge paints the territory of the sublime: moors, mountains, forests, the sea’s edge, the night sky filled with stars. But unlike Friedrich’s paintings, which are invariably populated by solitary figures that fill the foreground with their contemplative presence, her landscapes are devoid of human occupation. For Romantic artists the sublime was to be found in spectacular vistas, dramatic scenery and super-human geography. They drew the viewers’ gaze to a distant, unattainable horizon, evoking a sense of the transcendent, separate Other. Partridge’s subjects, however, are more mundane: moors engulfed in a blanket of fog; the honeycombs of spume that disturb the sea’s edge; or the interlocking patterns of positive and negative space formed by tree branches. Our gaze is not captured by a distant horizon, but by a foreground detail. Yet in some of her recent works, these apparently ordinary places are transformed by the chromatic crystalline patterns that have been a recurring subject since her days at the Royal Academy Schools. Within the empty air, in the space that lies between, we glimpse fragments of a geometric structure; subtle triangles and polygons that ripple the blue void with hints of an underlying substance. And along these pathways of colour we are led from the foreground into distant, vast horizons.

As a child, Partridge had had intense synaesthetic dreams of simple, brightly coloured geometric forms, which appeared to emerge from and move around a still central point. At art college these childhood ‘nightmares’ inspired a process of visual investigation arising from this feeling of wonder, which in turn led to visual knowledge. These then became new moments of wonder, which inspired further visual experimentation and discovery. Over time this ‘wonder cycle’ has seen the early kaleidoscopic vortices, with their brightly coloured squares, rectangles, spheres and circles become more sophisticated, developing into three dimensional forms and subtler colour systems that focus on a more limited palette of blues, or whites and greys.

Now these childhood moments of internal wonder, and their subsequent development into a refined visual vocabulary, have begun to seep into her everyday experience. Cezanne saw the structure of the physical world in terms of cubes and spheres. These same geometric forms lie at the heart of Partridge's crystalline vortex. But here they are not associated with tangible matter, instead they occupy the space between forms; providing a tantalizing glimpse of the invisible structure that lies within the gap. They reveal a rainbow bridge of light reaching out both away from Partridge and towards her, its waves of electromagnetic energy connecting micro and macro, self and other, bridging the difference between the immanent and the transcendent.

When we are confronted by an experience of the sublime, as we look out upon the indescribable vastness of the Universe, we feel overwhelmed by the infinite that confronts our gaze. We become lost in the immensity of time and space, just as we become lost in a tangle of branches, or the forest of stars that fills the sky. But as our focus shifts from the distance to consider the individual branches and stars we can find that time seems to stand still. Slowly the fear begins to dissipate to be replaced by a sense of wonder.

For as these paintings remind us, we find wonder in those incidental, fragmentary moments, those overlooked individual details, when darting, elusive rainbow flashes erupt for an instant onto the periphery of our gaze allowing the ‘macro’ to enter our individual reality. Rather than overwhelming us with intimations of the incomprehensible these small moments of insight allow us to feel a sense of direct connection with the transcendent and unseen; inspiring us in turn to reach back out with our gaze, our imagination, and our inquisitive desire to uncover what is hidden.

In the small patterns we might discover in spume, in the stars, between branches and leaves, and at the boundaries of rock and ice, Partridge finds those rare instances of insight that afford glimpses into the space between, a momentary revelation of a continuum uniting the individual microcosm with the larger macrocosm of which it forms only a minute part; shards of everyday wonder rather than moments of fear.

Revd Dr Richard Davey - July 2011

The Revd. Dr Richard Davey is an Anglican Chaplain and Visiting Fellow in the Visual Arts, School of Art and Design, Nottingham Trent University. Richard’s research focuses on the way in which faith, as a distinctive and counter-cultural world-view, is embodied and materialised within works of art.

In The Daytime

Watercolour on paper, 100×80cm, 2011

Stikkisholmur Sky

40×50cm, oil on birch ply, 2011

Bavarian Forest

Oil on board 24×30cm 2010

Glacier Fog

40×50cm, oil on birch ply, 2011